Products You May Like

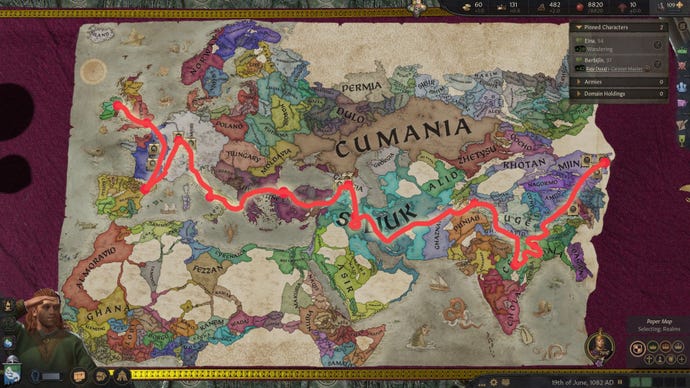

We pitch our tents outside Constantinople and crack open the ale. In the light of the campfire I examine my travel companions as they party. There’s an Ashkenazi rabbi, a Saxon serf, some French knights, a Czech spy, a German dwarf, and a pair of inseparable Italian peasants. This rowdy band of roustabouts I’ve collected in the Crusader Kings 3‘s Roads To Power expansion has the feeling of a found family, each fellow wanderer sporting their own ambitions and quirks. They won’t all make it. Many of the people I’m looking at in the glow of these embers will fall on the road, victims of robbery, landslides, and animal attacks. One of them will sacrifice their life to save the rest of us. All will bring me a step closer to my goal: I am walking from Ireland to China.

The Roads To Power expansion introduces a lot of neat Byzantine empire stuff. But the real attraction, for me, is that it also now lets you become a “landless adventurer”. I’ve already written about how this completely changes the game. Here I’ll be experiencing the adventurer’s life first hand. Following the example of Marco Polo and Ibn Battutah, I’ll use the character creator to rustle up a strong Irish lad who wants to see the world. His name is Cathmál a hÉrinn.

Although I ensure Cathmál is a well educated country Gael, he will also turn out to be incredibly horny. As an 18-year-old pagan born out of wedlock in 1066 with no claims to any land of his own, he has good reason to go wandering. The character creation screen of CK3 is well-stocked with useful traits and characteristics we can take advantage of. Cathmál is thrifty (good at earning cash), impatient (travels 25% faster than normal) and brave (100% more likely to die horribly in a battle). He is the leader of a new band called the “Turbulent Travellers”. His emblem is a salmon. It is symbolic of travel, fertility, and tastes great with rice, although he does not yet know what rice is. His motto is “China or Death”.

There are plenty of other skills I could pump into our young friend, but part of the appeal of an adventurer’s life is to gather flecks of personality as you roll along, like sugar on a fresh donut. The journey will make the man.

With all the preparation done, I recruit some friends and set out for the exotic land of Wales. One of my oldest pals, a violent brute called Fothad the Hawk, comes with me. He is described as “significantly more likely to harm others”. I love him dearly.

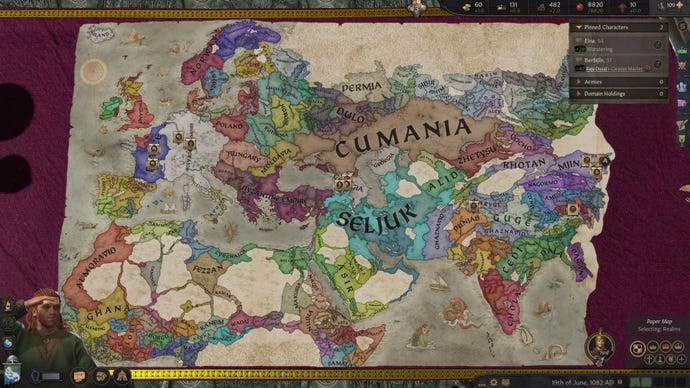

To move from place to place you click on a county and press a simple “travel” button. The map changes into “travel planning” mode. Every act of relocation sees your wee figure strutting over the world map. This uses up provisions, a foody currency that acts as the material representation of your campmates stuffing their faces with apples scrumpied from nearby orchards.

But more often said apples are earned through contracts. Intimidate a local tax dodger, say. Or build a tower for a noble as a phallic symbol of his power. These can be as simple as choice-heavy prompts with lots of skill checks, or as complicated as multi-step schemes. To keep contracts fresh, you have to keep on the move.

It’s a big contrast to how Crusader Kings is normally played. It sometimes feels like the horsey vagabonding of Mount & Blade (a series that itself could be described as: “What if Crusader Kings but in third person?”). As a fan of both games, playing as an adventurer makes me deeply giddy. Especially when Fothad gets himself into a fight with a Welsh man on the way to London.

Fothad the Hawk is a wirey 30-something Celt with a fickle temper. His opponent is a fully armoured knight errant. As an 18-year-old, I decide Cathmál won’t get between them. Fothad, the absolute legend, doesn’t need armour to do a big stab, and the Welsh fella is slaughtered in the fray. We should probably leave the country.

This might have been avoided. When you plan a trip, you can see the likelihood of scrapes you’ll get into along the way. The map becomes colour-coded, showing war torn regions and hot spots. Gloucester has some dodgy looking bandit forests, for example, where “many travellers go missing”. Luckily you can customise your route by adding detours, region by region. You can also buy a “wilderness kit” to prep you for forest terrain, or hire mercenary guards. For now, we’ll simply go a little further north, around the forests. This eats up more provisions and adds only a few lower-risk encounters. It’s a pattern of travel I’ll repeat throughout the game. I’m sure the roads of England will be relatively safe though, right?

What follows is a journey marred by four vicious attacks including wild animals, muggers, and a beautiful gaelic assassin hired by an English lord who simply didn’t like the look of us as we passed through his fields. (I keep meeting gaelic people everywhere I go; this is generally the case in real life too). By the time we reach London I am brutally injured, probably about to die, and having (presumably painful) concubinal sex with a physician I picked up on the outskirts of what is today Slough. She, my friends, is also a gael.

In my pain, I look at the calendar. It has taken a YEAR to reach the English capital. This feels like terrible progress. Battered, poor, and on the run, I remember that I’ve also made Cathmál a “journaller”, which means he can write to soothe his mind. He dips the quill and thinks of distant China, wondering if his goal is truly possible…

1067

Cathmál has recovered from his wounds, and prepares the troupe for a departure to Europe proper. His brush with death has given him some perspective. Perhaps it is time to choose an heir. He chooses the doctor he is fucking.

1068

The gang has arrived in Barcelona, on a mission to escort an emissary from Bruges to the court of a Catalan duke. Everyone in the hot city is coughing. We throw the sick emissary into the duke’s lap and prepare to leave before we too catch the “Barcelonian Sweats”.

1069

We camp outside the walls of Klingenberg, home of the Holy Roman Emperor. We host a “revelry” to reduce everyone’s stress, and invite the Emperor himself to eat and drink with us. He does not respond.

1070

Cathmál has, for some reason, enrolled in a university program in Rome. He studies so hard he nearly has a mental breakdown. But then two Italian peasants, Carlo and Lealdo, break into the uni and start getting sloshed on the monk’s wine. They teach Cathmál to relax, and become good friends, joining him on the journey.

1071

On the way to Greece, we are hounded by a terrible new beast called the “mosquito”. Fothad, the absolute mad lad, gets his shirt off and acts as a kind of sacrificial blood magnet for everyone. His pecs no doubt glittering with red speckles, he remains the unbeatable himbo of the troupe.

1072

We host a party outside Constantinople. We neglect to invite the Emperor (or his mysterious co-Emperor). Neither is offended.

1073

We arrive at the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, where Cathmál is pained to discover he must wait many years for the “attend university” decision to “cool down”. Thirsty for knowledge, or maybe something else, he instead starts learning Greek from a woman the band picked up in Thessaloniki.

1074-1075

Our gang of Western weirdoes spends a whole year in the court of local ruler, Agha Abd Al-Hamid, serving as his “entertainment”. We are forced to leave when the courtiers grow tired of us, claiming our stories are ” a pack of lies”, which is only partially the case.

1076

On the banks of the Tigris, we are surrounded by bandits. An Ashkenazi champion, Menashe, steps forward and tells the rest of us to flee, he will take care of this rabble. He dies heroically. Without his intervention, Cathmál would have perished.

1077

In the bars of Kabul, I go to see a storyteller. Every city has one. As a detached listener, the player only ever catches the very last lines of these tavern tales, usually a glimpse of some myth from around the world. Here, in Kabul of all places, Cathmál hears again the legend of the Irish giant Finn MacCool, told by a gluttonous yet warlike Afghan woman glugging violet sharbat. I like to think that it was a reminder to Cathmál that the world is connected not only by trade wagons and winding paths but by stories, tales travelling down silk roads as easily as cashmere and coin.

1078

Three friends get eaten by a tiger.

1079

The travellers pitch their tents in the shadow of Mahabodhi temple, the site where the Buddha is said to have reached enlightenment. Everyone gets drunk.

1080

After a year of working here, the sights, sounds, and smells of Bengali life call powerfully to Cathmál. Here he stands, on the cusp of his goal, with the splintered lands of China lying just beyond a single mountain range. And yet the Buddha smiles warmly at him, teasing a life content with what he already has: friends, peace, green fields, roots. Perhaps it is enough to be satisfied here. Does he really need to see another country? To meet yet more people? To chase yet more of the shifting earth?

1081

Yes. He does. A full 15 years after Cathmál set sail from the shores of Ireland, our boy lands in the city of Xingqing, capital of the Mjinjaa kingdom and one precursor to modern day China. He immediately gets to work seducing the King’s wife.

Epilogue

So. Cathmál made it. And importantly, so did his friends, his many lovers, his children (he had two along the way, real rascals), and his best buddy of all time, the jolly murderer Fothad. Others were lost along the way. Ernst, my dwarf quartermaster and one of the most competent people I will ever meet in this life or in real life, disappeared in a landslide. So did Carlo, one of the kind Italian pissheads. They were not the only losses. I probably lost more followers to mountain-climbing accidents than I did to war, hunger, or banditry put together. Alongside the death, illness, frostbite and aches, my fellow travellers also suffered many year-long hangovers. One or two of them adopted pets.

I cannot stress how much of a good time I’ve had with this DLC. Only building a multicultural empire of turtles and insects in Stellaris has brought me more entertainment in a Paradox game. Yes, it can get repetitive as you dismiss some of the same dialogue boxes over and over. But there’s still a good variety of events (and this was me playing entirely legally – without accepting any of the well-paying “criminal” contracts).

“Travelling gives you a home in a thousand strange places, and makes you a stranger in your own land.” It was the big lad, Ibn Batutta himself, who said that – aka, the original Lonely Planet travel writer. Which reminds me: there’s one more thing you can do as a traveller in Roads To Power, provided you meet the hefty requirements. You can write a book of travels.

Cathmál has already done this (he got started in India). His heirs can now inherit this book, granting them a hefty learning bonus. It’ll be useful for his whelp of a son and waif of a daughter. After all, Cathmál might not make it back to Ireland himself. Indeed, some say he never made it to China at all, that he was stabbed to death by bandits on the banks of the Euphrates. Others swear he was the one mauled to death by a tiger in the foothills of Kasmir, not his entourage; that he carries around a dark scroll entitled “save file” that gives him an uncanny ability to persist. Slander! I won’t have it. Our boy made it to his destination by the skin of his own motto: “China and/or death”.

He has written the tale to prove it.