Products You May Like

Strategy games are the go-to option when you’re looking for something to really get your brain working. But they can seem unreachable when your synapses are being melted from without rather than through overuse. Happily, we found an excellent solution last summer, and being a wily fox, I had a plan ready for this year. 2022’s now-traditional Low-Intensity Strategy Game For When Burny Light Make Think Hard is, of course, The Battle For Polytopia.

Polytopia happens to have a fair bit in common with Legion War, which perhaps suggests that the predictable, momentum-based nature of the 4X will make them an LISGFWBLMTH fixture. 12 civilisations are vying for control of a colourful little 3D pixel world, starting out with a humble village and solitary warrior for capturing rival villagers with which to produce more and better soldiers. Each village produces stars every turn, which are swapped for technology and the buildings you place on the map. Most of the latter are various flavours of harvesting resources, which adds population to the nearest settlement. There’s no automatic growth (technically barring a few buildings that develop over time), so improving your holdings is entirely your job.

Increase the population enough, and a village will level up, allowing it to support more soldiers, and offering a choice of boon, the attractiveness of which will often depend on the map and circumstance. It’s all pretty standard 4X, essentially, but it’s almost an ideal form of 4X. Where Legion War paced its complications, Polytopia largely removes them. It distills the concept, but retains just enough detail and strategic options to still feel somewhat meaningful.

Best of all, though, is its pacing. You know that thing where you leave a game partway through, then by the time you get back to it you’ve lost track of what you were doing, or just wind up starting all over again? That’s never going to happen with Polytopia. Well, maybe if you play the biggest maps. Don’t play the biggest maps. The standard setting gives it away: not only are the maps small but the duration is limited to a tiny 30 turns, after which whoever has the highest score wins and the game’s over. You can’t even continue with the score switched off after that.

There is a more traditional Highlander mode, of course, which also offers bigger maps that are better tailored to fit the full roster of civilisations. I’ve had plenty of fun with that too, but the standard mode really highlights that this works best when matches are over in, oh, half an hour, maybe 45 minutes. I’m rarely a fan of score attacks, and being declared the best in the universe because of some arbitrary point system has particularly bothered me in 4X games, but this one’s all about low pressure, disposable campaigns where losing is never crushing and winning never becomes a chore you have to grimly see through to the end. Except on the largest of maps, but some people may enjoy those large scale, light wargame operations about complex manoeuvres and shifting loads of units to the front. It helps that the points system rarely grants victory to a side that wasn’t very likely to crush it either way, although an option to take, say, five more turns to settle a photo finish might be entertaining. But perhaps it would merely water it down.

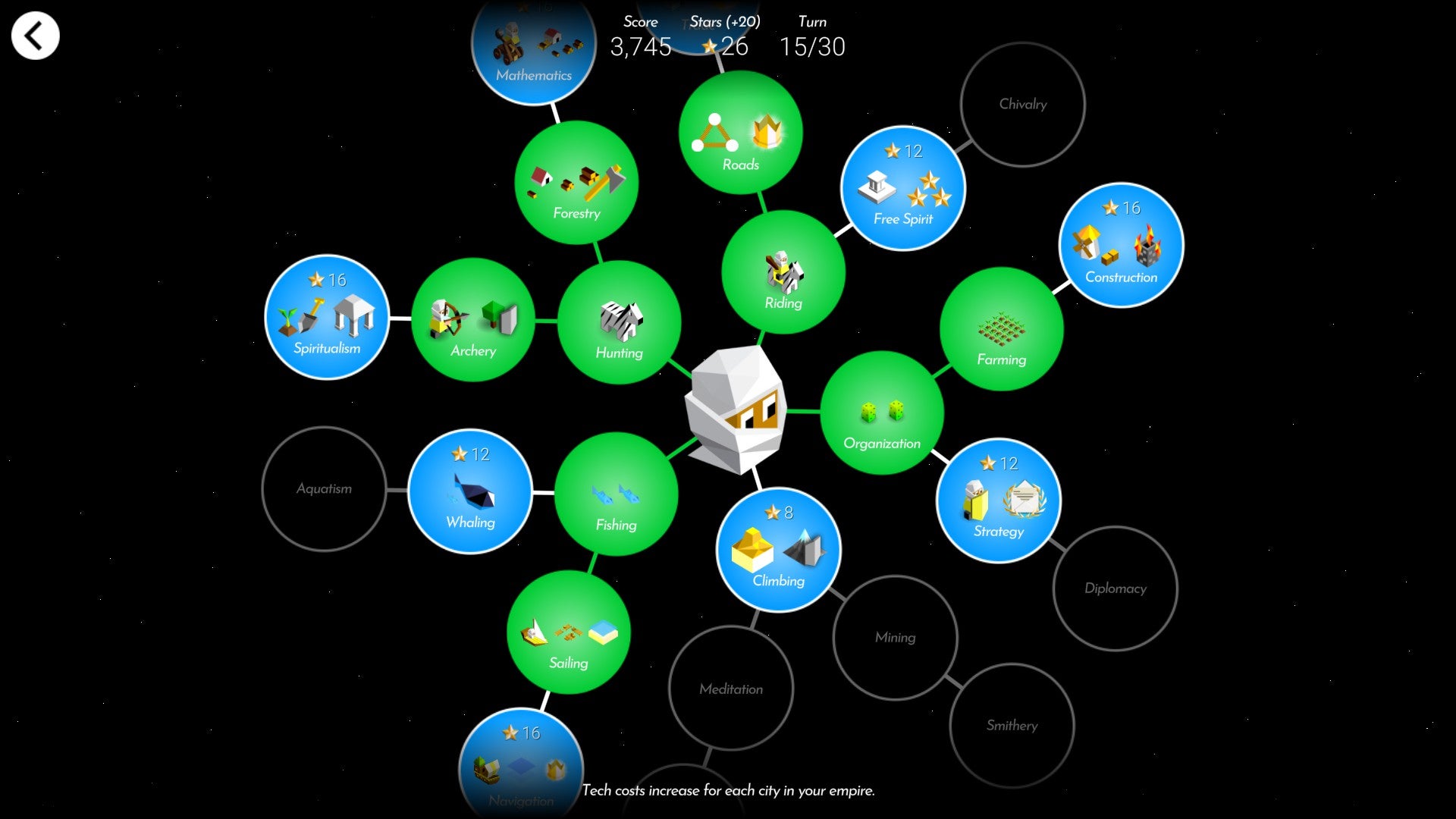

For the most part, each civilisation is the same, except each starts with a different technology. A few special DLC civs aside, everyone can research everything anyway, but even this simple difference can matter a lot. Every form of growth is paid for by stars, which are especially limited early on. Training units takes resources away from unlocking research, or improving a city, so if you start out with archery unlocked they’ll naturally be the core of your army for half of the game. Even if they’re not as good as riders, spending stars on that technology (and the riders themselves) is an extravagance that might cost you by leaving an early city under-developed or your army a little weaker.

The randomised maps have a similar effect, as your research priorities will be altered by local terrain. The Defender unit’s strength is obvious, but if you start without, it’s a costly two items into the research tree (which is really a small sea urchin, whose half a dozen spines have three items on each). Similarly, the mountain-based bonuses it offers may not be worth it when you could go after sailing instead. Then there’s the question of what your neighbours start with – the outcasts with their strong swordsmen are a different prospect to the Sherwood-ish side who start with archers. This can be frustrating, as you can get a start that just doesn’t give you a great chance, although admittedly this probably means you put too many sides on the map. You can never found a new city, only take them from enemies or, on less contested maps, recruit inert neutral camps into loyal villages.

Combat itself is straightforward. Beyond your unit choice, strategy generally comes down to prioritising your rivals so you can overpower them in turn rather than get caught on too many fronts. Tactics, meanwhile, is largely about working out your attack order. Each unit counterattacks any attacker if it survives, barring natural exceptions like lacking a ranged response. Most melee units automatically occupy the enemy’s square if they kill it, so you’ll often want to wear targets down with strong attacks then have a good defensive unit push in for the kill. But there are wrinkles. Riders can withdraw after an attack, mind benders can convert a target, and spies can incite rebellions at a city that summon several dissidents who can’t be counterattacked.

Everything does one or two simple things, and statistics are kept to basic 1-4 scales for attack, range, movement and defence, plus a few simple special abilities. It means that turns are never very long, and fights take a little thinking over but no strain or advanced calculation. When you select a unit, any target in range that it’s guaranteed to kill in an attack plays a little sweating animation to help prioritise and keep things moving.

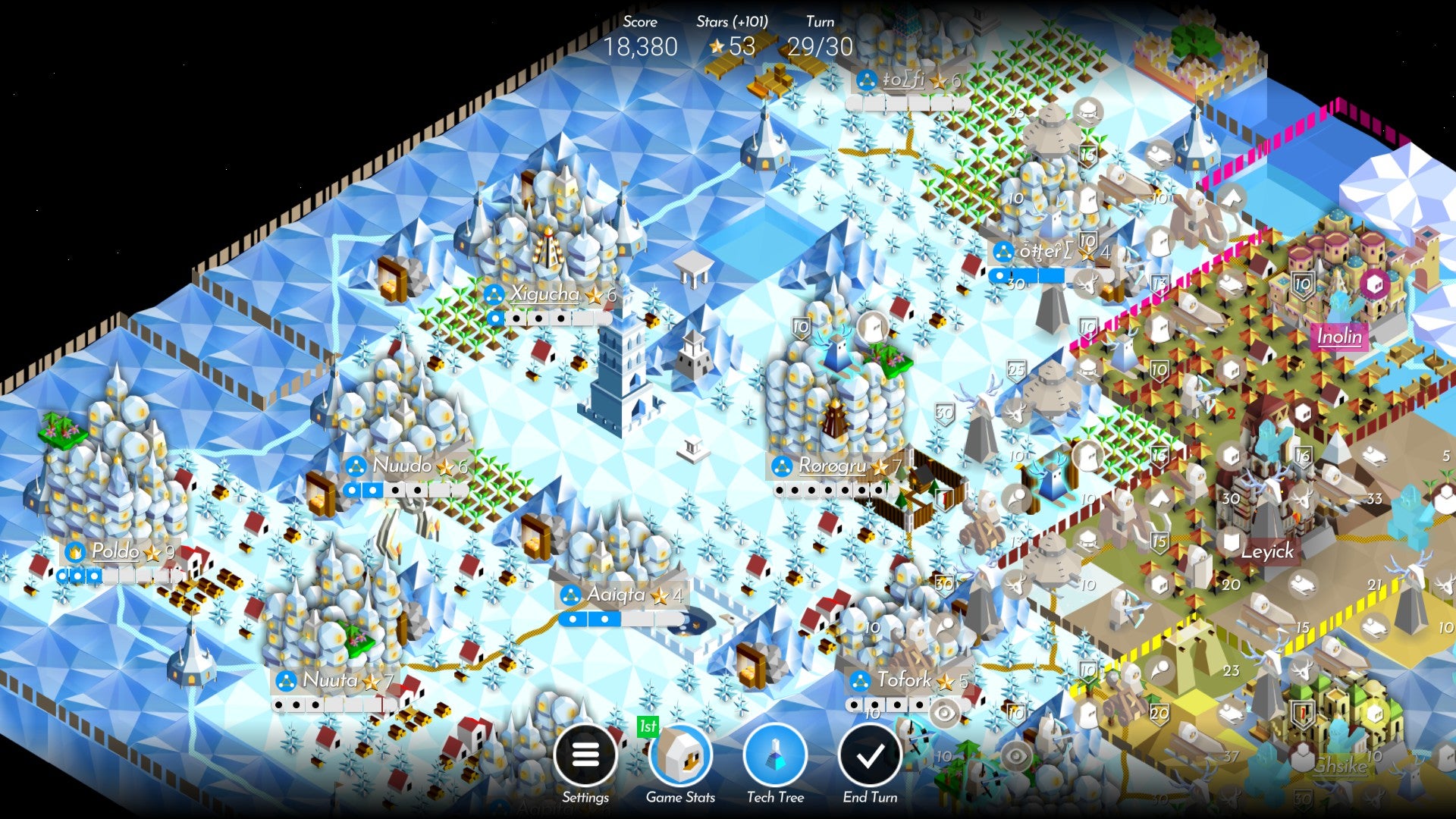

Every unit – every tile, in fact – looks excellent, too. Each faction is themed after a real world / fictional but familiar group or region, and all their cities and units look unique to fit their theme, even when their stats are identical to another faction’s. The very terrain flips over to your home biome when conquered, giving loads of visual variety and colour as well as an immediate representation of who’s doing well.

This does, however, lead to probably Polytopia’s biggest problem, which is severe cluttering once everyone’s well established. The art is lovely but very small, and I keep wanting to zoom in just a little more. The real issue, though, is that once everyone’s built loggers and temples and mines everywhere, it gets harder to see what’s underneath, yet to be untapped. Cities growing taller as they level is rewarding, but adds to the obscuration. All the armies running around get in the way, too, and require a second click on every block of terrain you want to check (which invites accidental move orders as both ‘select’ and ‘move’ are bound to the same button). It means that by the late stages, once my early cities have leveled I tend to stop leveling them, thus losing out on more score and the valuable ‘super unit’ option that’s really your only chance in some wars.

Polytopia attempts to work round this by unintrusively (and optionally) prompting you with a little sound effect and icon floating over a square that could host something. But there’s no way to dismiss that and move to the next, nor to tell a well-positioned unit to stay put, so the notification will focus on that one unwanted suggestion.

With all that said, mega-optimisation isn’t necessary outside fierce multiplayer matches, and unless you’re going for high scores, the points don’t matter much as long as you’re leading. Above all, Polytopia feels unstressful. There’s never too much to think about, never too many chores, and between the cheerful cartoony atmosphere and low-stakes matches, any disappointment or frustration is quickly forgotten.

It’s other shortcoming is its somewhat limited variety. Individual games don’t often last long enough to wear thin, but playing it back to back for long periods could leave it feeling very tapped out. The four DLC factions help here, adding some unique units and abilities and resulting new playstyles. The snowy ones in particular are a coin toss between getting crushed early due to starting with a defenceless utility guy and no directly useful research, and reaching critical mass of units with freezing power that will inexorably sweep through anything. The swamp people, meanwhile, replace the standard giant super-unit with a giant Snake, like from your granddad’s phone, that grows larger with every kill and can become a liability by blocking half the map from your own forces.

It’s enough, I think, and the additions are welcome, but I don’t think the repetition is a fatal problem. Most games get wearying if overplayed, and strategy games setting you all the way back to the beginning can feel particularly exhausting. Polytopia isn’t meant to be mainlined, though, and at worst you’re still looking at under an hour to go from hamlet to Hammurabi. Analysis paralysis just hasn’t been a thing for me here, and I’ve not hesitated to go back in for another quick go all week. Contrast that to the anticipatory exhaustion I’ve felt when looking at multiple alternatives, and it’s clear that the Battle for Polytopia is the only strategy game that stands a chance of carrying us through to the floods.