Products You May Like

Ho, wayfarer! Beware slight spoilers for Alan Wake 2 in the passages ahead.

Deep in the Dark Place of Alan Wake 2 there is a forest that is not a forest – a zig-zag tunnel adorned with murals of a grisly woodland scene. Entering that tunnel, you find yourself sealed in at either end. But the mural suggests a way out: it changes when you turn around, following an unspoken narrative. It’s a device as delicate as the graffiti elsewhere in the Dark Place is obnoxious. In hindsight, it feels like an example of “metsänpeitto”, a concept from Finnish folklore about forests which, as writer Sinikka Annala explains, saturates the design of Alan Wake 2. It’s a fascinating idea I’d love certain much larger, less intriguing video game worlds to learn from.

Metsänpeitto refers to “the forest’s cover”. It means “the state a person or an animal gets in when they lose their way in the woods, due to some trickery by forest spirits, and become hidden by the forest itself,” Annala tells me over email. Wanderers caught in the spell of metsänpeitto may become invisible to others, or at least, unidentifiable, like stray “parts of nature” lost within a purgatory of twig and bark.

“The people covered by the forest often would not recognize their surroundings even in familiar locations, might walk in circles, or might become frozen in place, unable to speak or move,” Annala says. “In some versions [of the story], the forest’s cover might also appear as an inverted, upside-down space. The metsänpeitto would often also distort sounds or be void of natural sounds altogether. But for the people searching for the missing, everything would appear normal.”

The enchantment of metsänpeitto can’t be escaped. It must be dispelled, defused. “To get out of the forest’s cover, the people looking for their loved ones would have to perform certain ritual-like tricks that might reveal them,” Annala goes on. “These include looking through the knotted roots of a tree or using specific rhymes to break the spell. For the person lost in the forest’s cover themselves, there are tricks like turning their clothes inside out or creating footsteps moving in a backwards direction that could help them return to the normal world.”

Annala caveats that Alan Wake 2 isn’t a literal recreation of these scenarios – the game amalgamates metsänpeitto with many other cultural influences (not least, it continues Remedy’s long love affair with Stephen King and Twin Peaks). But you can see the influence of this “magical thinking” on the game’s Dark Place, which is to some degree a lumpishly postmodern forest of words, and upon the interdimensional, verdant Overlaps where protagonists Alan and Saga first encounter each other. You sense it, too, in the forest puzzles that ask you to play out macabre fairytales by arranging dolls. You can see it in passing effects, such as the swaddling of enemies in defensive optical distortions that must be seared away with a torchbeam, or the silhouettes that appear projected from behind the player, like the shadows of Plato’s cave.

“Numerous parts of Alan Wake 2’s design and story relate in some way to the core concept of metsänpeitto, to the idea of traversing parallel spaces using dream logic and rituals,” observes lead writer Clay Murphy. “The light shifter puzzles in the Dark Place change the environment into different versions of itself. Saga has to navigate through three distinct loops of an Overlap, each one slightly different, to reach its centre. Saga and Wake see glimpses of one another between realities at the end of an Overlap or murder site. These are all speaking in some way to the idea of different realities touching our own.”

I’m not aware of any English myth that maps directly to metsänpeitto, but I certainly recognise the concept from my own walks in the woods. The classic mistake you make, on entering a wood, is trying to travel in a straight line. The wood may allow you to think this way, at first, offering up established paths and the suggestion of a living architecture leading securely towards distant spots of sun. But the path is not truly straight – it meanders gently under cover of the play of verticals. The trees may resemble pillars, signposts, but in practice they are oblivious, spiralling vegetal forces that pull you around them like planets, launching you away at unexpected angles. Not for nothing are forests portrayed as essentially sorcerous places in so much fantasy literature, from the midlife undergrowth of Dante’s Inferno to Robert Holdstock’s fermenting masculine daydream Mythago Wood, in which the outermost trees form “vortexes” protecting a timeless core.

You can follow that literary lineage into video games. I’m no coder, but I get the sense that forests are fiddly propositions for developers. Trees are flexing and fussy organic structures, occupying an annoying hinterland between predictability and randomness. They repeat enough to threaten monotony while remaining fundamentally dissimilar. Leaves constitute hundreds and thousands of smaller, dispersing shapes, not quite the tree, not quite themselves. They tinge and burst and sculpt the sunlight in ways that seem as faffy to engineer as they are glorious to behold.

Developers cheat, of course. Every video game forest is fundamentally a garden, pegged out according to the needs of a story or quest or puzzle or the frame-rate. But the greatest such virtual forests, for me, are those whose creators lose themselves in the woods alongside the player – whether by scattering the trunks according to research into growth patterns, or by means of analogous, quasi-fairytale structures which video games are uniquely equipped to provide. Take the Snowfly Forest of Vagrant Story, whose clearings link up rhizomatically in ways hinted at by each area title, so that finding your way through is the act of reorganising an atomised electronic poem.

As spaces where boundaries sprout and disintegrate and everyday laws are suspended, forests are also ideal, haphazard meeting places for things that might not “fit together”, in some sense. In the case of Alan Wake 2, the forests aren’t just Overlaps between the living world and the Dark Place, between Alan and Saga, but between North American and Finnish mythology.

“Mythology and folklore around the world is all attempting to explain the same core fears and unknowns,” Clay Murphy goes on. “While we may not have a concept as specific as metsänpeitto, folks in the USA are plenty wary of the woods. Our version tends to revolve around monsters that lurk in our local forest. A man with a hook for a hand, the Jersey Devil, a serial killer from a nearby prison, that kind of thing. This American fixation with a boogeyman in the woods can be seen in the Cult of the Tree, lurking in the forest with their knives and creepy masks.”

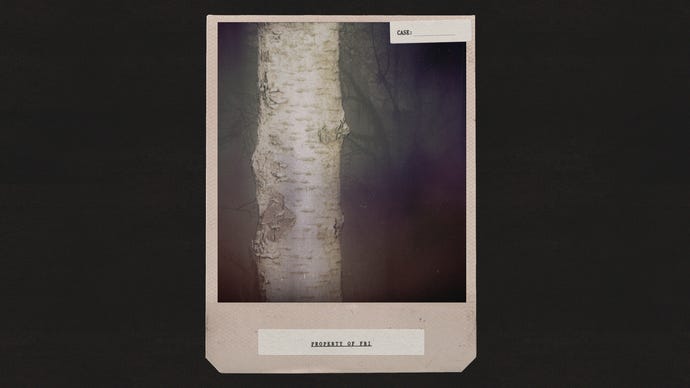

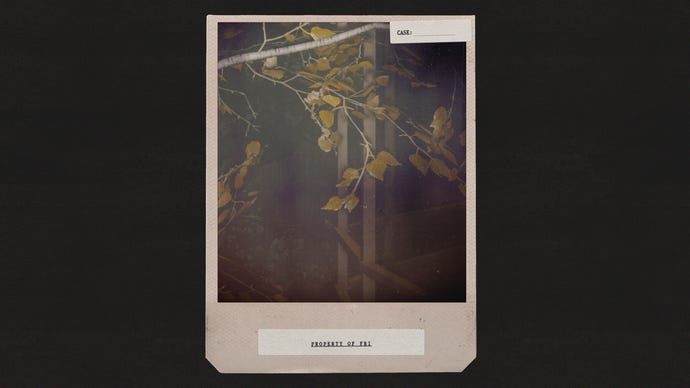

The game pursues this particular Overlap in the specific choice of trees, which draw upon both Remedy’s research trips and surveys of Washington state’s Pacific Northwest biome, conducted by park rangers, arborists, and nature conservationists. You notice it especially in Watery, the lackadaisical fishing burg just down the road from Bright Falls, which has a stronger Finnish identity. “There are a lot of birches in Watery,” says foliage and photogrammetry artist Ciara Creagh-Peschau. “This was a really big part of visually evoking Finland and the birch forests we have here. Birch trees represent protection from evil in Finnish folklore and are also a really important building material and for medicinal use, so we felt it would make sense for the Finnish immigrants of Watery to plant lots of them.”

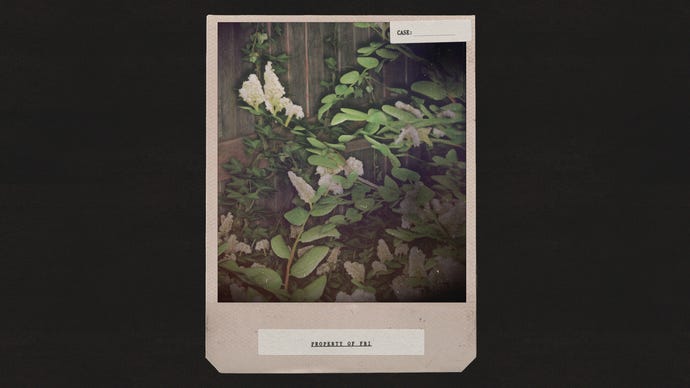

The murky shores of Cauldron Lake, meanwhile, are defined by trees that feel “primordial, threatening, and timeless”. This area is heavy on Douglas firs, which have a reputation for weathering forest fires. “It’s a bonus that they get a shout-out in Twin Peaks as well!” Creagh-Peschau notes. There are vine maples, used by native American basketweavers, which have an undead aspect here. “They’re very snake-like and draped in lichen and moss which again creates this hostile feeling of hands reaching for you.”

And then there is the monstrous, ruined trunk in the forest’s heart, a place of witchcraft and a portal to one of the Overlaps. “I know that for the Witch’s Ladle we wanted to represent one of these petrified red cedar trees that often have stories of warning or sacrificial sites attached to them – think that one spooky tree in the forest where kids dare each other to get close to it,” Creagh-Peschau recalls. “That being said, red cedars are also a symbol of eternity and are considered a tree of life to various indigenous tribes in the Pacific Northwest; this was significant again to reinforce that sense of Cauldron Lake being this primordial place that exists outside of time.”

Alan Wake 2’s handling of Native American culture is a topic I’m not equipped to explore – I would like to read an account from somebody who is. But the spectre of colonialism here does create an Overlap or at least, a fruitful contrast between Alan Wake 2’s forests and a very different type of simulation, the open world. If forests are places of misdirection and glamour, suspension and disarray that can only be navigated by means of “ritual-like tricks”, modern open worlds favour a creed of ultimate exposure and crushing, A-to-B literalness. They aren’t flat planes, but they tilt toward the idea that everywhere and everything must be visible and accessible. The world is a space to be mapped, not a spell to untangle. The geography harkens back to the triumphal linear perspectivism of European imperial art, where the eye sees as the cannonball flies.

There are woods in open worlds, of course – Kingdom Come: Deliverance is one that commits to a sprawling, naturalistic representation, and I have had a fine time foraging for mushrooms beneath its boughs. But there is rarely the possibility of falling under the forest’s spell. The only game I can think of that seriously tries it is Breath Of The Wild, whose Lost Woods area effectively shelves the open world, and mires you in an endless series of walks between campfires – a limbo reminiscent of that underground tunnel in Alan Wake 2, which must be unravelled rather than traversed. Perhaps if more open worlds permitted their designers to wander in this fashion, they’d be more enchanting.